Reading for Pleasure: What, why and how

Posted on 15 February 2022

Are you seeking to foster reading for pleasure in your classroom and/or school? If so, are you sure what this means and how to achieve it? Is it just children listening to stories and enjoying them? And why are you working towards this goal in any case? What are the long-term benefits of being a keen reader in childhood? This article responds to these questions, explores the challenges you might face and signposts you to additional resources and courses that can help. Do read on!

What is reading for pleasure?

In essence, Reading for Pleasure (RfP) is choosing to engage with texts for your own recreational purposes in anticipation of some kind of satisfaction. It is the reading we do for sheer enjoyment, for relaxation, for the emotion we experience or the information that we seek. In the UK, RfP is the term commonly used, but in other countries ‘voluntary reading’, ‘leisure reading’ or ‘recreational reading’ often refer to such free-will reading.

When children find texts they enjoy, (in print or online) they want to read more. They seek out other books by the same author or in the same series, read particular comics and magazines regularly, or pursue with a passion information about their favourite football team, pop group or endangered animal, for instance. Children’s engagement with particular characters, thirst for knowledge about the world, and response to the emotional power of texts drives their desire to read. All of this depends upon their access to texts that tempt, that invite and that sustain their engagement. They are motivated to keep reading (or returning to) these texts because intrinsically they are relevant to them and their friends.

Historically, reading has been seen as a solitary activity, but in the 21st century there is a much wider recognition of the social nature of reading and a realisation that friends and family, teachers and peers, play a key role in supporting and enabling the beneficial habit of reading in childhood. For adults too, reading for pleasure is both solitary and social, we may read a novel or a newspaper alone, but later we are likely to chat to others about what we’ve read, about the issues raised, and the connections to our lives. Such conversations support us as we make meaning from texts, just as the shared social experience of being read to and talking informally about texts nurtures the sense making of younger readers.

So RfP is always dependent on the text being read (its quality, potential for connections, interest level and relevance to the reader) and the social context (who else is present, where the reader is, what opportunities there are for interaction). But why is it worth developing children’s desire to read?

Why nurture children’s reading for pleasure?

Young people who choose to read regularly and widely give themselves built-in advantages. International evidence indicates that RfP has multiple positive consequences. It is associated with increased confidence in reading, greater engagement with learning, and better learning outcomes (Mullis et al., 2017; OECD, 2019). In England, analysis of the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS), found that those 10-year-olds who reported enjoying reading the most, scored, on average, 45 points more than those who reported not liking reading (McGrane, et al. 2017). Based on large-scale studies of teenage readers, the OECD (2021) also argue, that engagement in reading is not only strongly correlated with reading performance, but that it is ‘a mediator of gender or socio-economic status’. As such RfP is a social justice tool that can help to redress early difficulties or disadvantages and foster social mobility.

being a keen reader nurtures children’s social and emotional development, enhances their imaginations and can foster their capacity for empathy and understanding of others’ lives, potentially leading to compassion and social action.

Through ‘just reading’ to themselves regularly and widely, children are introduced to and later use richer vocabulary than their peers who do not choose to read (McQuillan, 2019). They also encounter new knowledge and understanding about the world and are able to draw on this in their writing and learning right across the curriculum. As Stanovich (1986) accurately observed ‘reading makes you smarter’. Furthermore, being a keen reader nurtures children’s social and emotional development, enhances their imaginations and can foster their capacity for empathy and understanding of others’ lives, potentially leading to compassion and social action. If teachers are positioned as readers too, then children benefit from new reader-to-reader relationships with these significant adults and gain support through the classroom reading community (Cremin et al., 2014; Merga, 2016).

Research also indicates that what children read and the amount they read matters. Perhaps unsurprisingly, fiction is more closely associated with higher reading outcomes than other forms of texts (Jerrim and Moss, 2018). In relation to reading amount, or what Allington (2014) calls ‘reading miles’ – the distance travelled through reading – studies show that the more frequently children choose to read, the more invested they become, the more they enjoy it, and the greater the benefits they accrue (Torppa et al., 2020). In effect keen young readers give themselves additional reading lessons, ask more questions of texts and the world, and consequently develop as greater depth readers and active learners. This is why RfP is a key aim in the National Curriculum in England which states that all pupils need to ‘develop the habit of reading widely and often, for both pleasure and information’ (DfE, 2013). The impact of RfP is also highlighted in the government’s Reading Framework (DfE, 2021).

What challenges are involved?

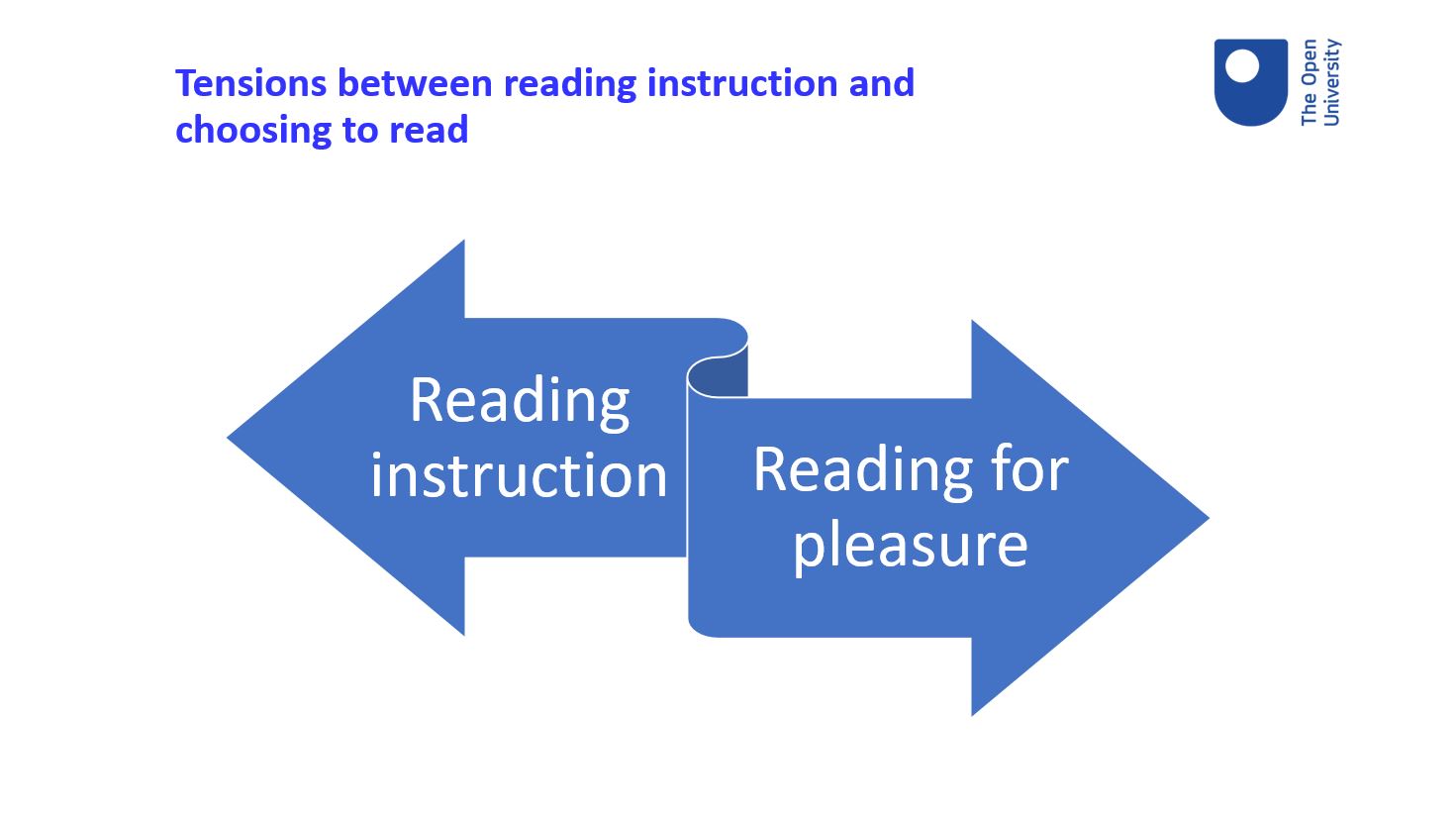

Despite national expectations and the evident benefits of being a keen reader, nurturing a love of reading alongside and as complementary to teaching reading skills can be challenging. In contrast to phonic knowledge, reading comprehension and fluency, RfP is not assessed – you cannot measure children’s pleasure! This tends to sideline choice-led reading, creating tensions between reading instruction and RfP. The backwash of assessment also constrains RfP pedagogy, for instance prompting teachers to misappropriate reading aloud as another opportunity for explicitly teaching the skills of inference and deduction (Hempel-Jorgensen et al., 2018).

A number of other challenges exist, not least of which is children’s attitudes to reading. In England, the number of children who report reading daily is at its lowest level since 2005 (Clark and Teravainen-Goff, 2020). Just 26% of under-18 year olds spent some time each day reading in 2019. International studies underscore this concern: in the last PIRLS study, England had the lowest ranking for pupil enjoyment and engagement in English speaking countries, except Australia (Mullis et al., 2017). Since the will influences the skill, this does not auger well for our young people in relation to academic outcomes, let alone potential social and emotional consequences.

Making time for RfP in school and finding the money to fund a rich range of diverse texts suitable for all children is also challenging. Additionally, teachers’ knowledge of children’s literature has been found to be limited, many are reliant on celebrity authors or books from their own childhood and where this is the case, it is insufficient to entice free-will reading (Cremin et al., 2014; Clark and Teravainen, 2017; Farrar, 2021). Furthermore, with the best of intentions, some schools seek to motivate readers by creating competitions, offering gold stars, bags of popcorn and reifying ‘readers of the week’ and ‘word millionaires’ for instance. Yet intrinsic motivation – reading for enjoyment, to find out or connect socially with others – is far more closely associated with RfP than such extrinsic motivation – reading for rewards and competitions (Orkin et al., 2018).

We need to ask ourselves as educators whose agenda are we serving? Surely our long-term goal is for children to become lifelong readers, not merely to reach the ‘expected standard’ in their eleventh year! But how can we achieve this?

How can we foster children’s RfP?

Given the benefits of RfP, children’s desire to read cannot be left to chance. Once they can read, children need ongoing support to become readers who actually choose to read. Far too many children have not yet found what reading is good for and remain disconnected and disengaged as readers. Young people deserve teachers who draw on effective evidence-based RfP strategies. The model developed during the Teachers as Readers (TaRs) research project (Cremin et al., 2014) revealed the knowledge and RfP pedagogy that makes a difference. It highlighted the need for responsibility, rigour and relevance.

When teachers recognise the professional responsibility to expand their repertoires of children’s literature and other texts, they get to know texts in depth, and can more effectively foster RfP. Such knowledge is key. Finding the time to expand your repertoire of children’s texts requires considerable commitment but is essential if you aim to develop children’s RfP. In particular you’ll want to ensure you know a range of contemporary texts that reflect the diverse realities of children’s lives. Children should be able to see themselves through the mirror of fiction, see others through the windows on the world that books offer, and be able to step through the sliding glass door of fiction to inhabit those worlds (Bishop, 1990). In this way empathy, tolerance and understanding are fostered. So, it is also a moral responsibility to keep up to date with children’s texts that are relevant in the 21st century – morally, emotionally and socially. For ideas on how to develop your knowledge and set yourself reading challenges, see: https://ourfp.org/finding/teachers-knowledge-of-childrens-literature-and-other-texts/

The TaRs research also indicated that teachers need to take responsibility to develop their knowledge of children as readers, especially reluctant or disaffected readers (Cremin et al., 2014). Without in-depth knowledge of children’s attitudes, histories and identities as readers, you will be unable to tailor your pedagogy and text recommendations to effectively support them. You will also want to learn about each child’s interests, the sort of reading materials (print and digital) that they might choose to read at home. This will help you avoid making assumptions about children’s preferences and enable you to gather children with common interests together for instance. You can use a range of strategies to find out about young readers, including reading treasure hunts, reading rivers, 24-hours reads, and surveys, leading to reading conferences, conversations and more finely tuned support. For more ideas see: https://ourfp.org/finding/teachers-knowledge-of-childrens-reading-practices/

This four-stranded RfP pedagogy ensures rigour is applied to supporting readers, and is dependent upon your knowledge of texts and of readers (Cremin et al., 2014). It is worth noting though, that the strands do not represent routines or timetabled slots, they are interrelated and shaped in response to the young readers’ engagement. In order to nurture a love of reading, you’ll want to support children’s autonomy as readers and create social spaces that encourages ownership of their own RfP. Thus, the principles underpinning this pedagogy include the extent to which it is:

- Learner-led

- Informal

- Social, with

- Texts that tempt.

This is your RfP pedagogy check-LIST, enabling you to plan reading time, read alouds and informal book talk around relevant texts that are likely to tempt the young people in your class, fostering their agency and social interaction as readers (Cremin, 2019). While you cannot require children to choose to read nor insist they gain pleasure from the experience, you can develop a rigorously planned and evaluated RfP pedagogy. In contrast, some school planning for RfP remains haphazard, with time set aside for relaxed reading only during reading alouds led by the teacher, World Book celebrations or when occasional authors’ visit. This is simply not enough.

This RfP pedagogy, which was developed from TaRs (Cremin et al., 2014) is endorsed by the NUT (2016), and by the DfE (2020) through their English Hubs programme. As the DfE summary indicates, reading aloud in order to nurture free voluntary reading, is in addition to reading aloud during comprehension or to support writing. Reading aloud to encourage free-will reading can helpfully become more LIST and involve the children in making choices of the texts that tempt them, perhaps through voting with counters for ‘Our Choice Fridays’, from the school-wide menu of recommendations or from a selection curated by the teacher of class novels. Children can also be involved in reading aloud to each other in small self-selecting groups or dedicated assemblies. In the process, they will encounter texts that engage and excite them and texts that they could not tackle fostering a sense of belonging through informal conversations about these ‘books in common’ (Cremin, 2019). Reading aloud in UK homes appears to be declining, particularly once children can read to themselves (Farshore, 2020), so it’s crucial to sustain this practice through from the early years to KS3. It’s important too, to consider how to follow through from reading aloud sessions to support choice-led reading. You could for example promote other books by the same author or on the same theme, making these available for later reading.

Space in school for independent reading time is another key strand of effective RfP pedagogy. Reluctant readers and those whose current book does not engage them, will not be able to make good use of this time, so thoughtful tailored support is needed (Moses and Kelly, 2018, 2019). This might comprise help for making informed choices, (through book promotions, displays and recommendations) and support to remain focused and develop stamina. Some children will also need support to voice their views about what they are reading. During this time, you could offer the children the chance to read, re-read, share books with others, read to others, discuss what they are reading and engage in books in greater depth. There is no one style of Everybody Reading in Class (ERIC), that fits all readers, much will depend upon your class’s needs. The space may be buzzy and noisy at times and quiet at others. Ensuring such reading time is learner-led is essential, so do encourage children to decide what to read, where to sit, who to sit alongside, and whether they want to discuss what they’re reading. To develop as an ‘autonomy supportive’ Reading Teacher, you will want to avoid holding the reading reins too tightly in this time, and to pay close attention to the children’s engagement and responses to their chosen books. Then you can build on this to sustain and stretch their understanding and pleasure.

Informal book talk and making recommendations is at the heart of RfP pedagogy, woven into reading aloud and reading time in your social reading environment. This is often spontaneous, involving teachers and children, and children and other children chatting about books. Again, it’s dependent on teachers’ text repertoires and knowledge of the children as readers. Initially, informal book talk may be more teacher-led as book blethering is modelled by you and other adults. Over time however, you will find that your ‘books in common’ or ‘book blankets’ act as stepping stones towards more child-led conversations. Gradually, such book talk will become more authentic, as children develop the agency and autonomy to share their views, and become more assured at asking questions, voicing connections and exploring interpretations. This ‘inside-text talk’ (Cremin et al., 2014) is an opportunity for rich thinking, where together children can co-construct their understanding of texts, based on knowledge gained from life and their experience of other texts, films and TV.

Reading aloud, reading time and informal book talk are significantly supported by the social reading environment, by the ethos and reading culture in the classroom and across the school. Successful environments promote the pleasures of reading and invite children to participate as readers. But this involves far more than creating a reading corner with cushions and fairy lights or a Starbooks or Netflix book display. While the physical environment does make a difference, their purpose is to support choice-led independent reading, and as the DfE (2021) Reading Framework highlights, reading corners are primarily for reading, for browsing and for blethering about books. The social reading environment is important ‘in which adults talk with children throughout the day’ (DfE, 2021). Such informal book talk supports children’s engagement, is socially motivating, and encourages positive attitudes to books of all kinds and an emerging sense of self as a reader. Social reading environments highlight that reading is a shared social activity that children can enjoy participating in with their peers.

Conclusion

If you aim to develop children’s volitional reading at home and at school, then you’ll want to exercise your professional responsibility to enrich your subject knowledge of texts and readers, develop a rigorous and monitored RfP pedagogy and ensure that the texts you offer are relevant to children’s realities and diversities. In this way you can begin to build communities of engaged readers which are reciprocal and interactive and include all children, parents and staff. Such communities shift reading from being seen as a solitary pursuit for some, to becoming a collaborative and engaging social practice for all.

Do you want more support?

If you wish to develop your understanding and practices, then, in addition to exploring the work of literacy organisations such as the National Literacy Trust, BookTrust, The Reading Agency and the Centre for Literacy in Primary Education, check out The Open University’s RfP work. The OU draws directly on a range of evidence in its dedicated RfP website and a wider coalition of Teacher Reading Groups, Higher Education partnerships and its Reading Schools Programme: Building a Culture of Reading. The practical website includes short classroom videos, practical activities, PowerPoints for PDMs and over 550 examples of teachers’ practice. The free monthly newsletter has over 45,000 subscribers. Do join in! https://ourfp.org

To widen your reading repertoire and classroom practice

- Participate in a free OU online course on RfP. Launching January 2022, this 8-session CPD course will enrich your knowledge, understanding and RfP practice.

https://www.open.edu/openlearn/education-development/developing-reading-pleasure-engaging-young-readers/content-section-overview

- Join an OU/UKLA Teacher Reading Group. Over 100 of these CPD for RfP groups run annually across the year. They comprise six free after school sessions, online, blended and in person, to support teachers in developing the knowledge and practice needed to enrich children’s RfP. https://ourfp.org/schools-teachers/teachers-reading-groups/

- Join the Teachers’ Reading Challenge. Run by the Reading Agency in partnership with the OU from June–September each year. Join a community of educators and readers to set your own reading goals, share recommendations, and discuss best practice. https://readingagency.org.uk/adults/quick-guides/teachers-reading-challenge/

- Read Book Award Winners. A summary of all children’s book award winners each year is offered to help teachers stay up to date. https://ourfp.org/2021/12/02/book-award-winners-2020-21/

- Read Books for Keeps. This independent children’s book magazine reviews hundreds of new children’s books and publishes articles on every aspect of writing for children. http://booksforkeeps.co.uk/

To extend your reference reading

- Cremin, T., Hendry, H., Rodriguez-Leon, L. and Kucirkova, N. (forthcoming, Summer 2022) Reading Teachers: Nurturing reading for pleasure London: Routledge

An accessible new book enriched with 24 Reading Teachers’ voices and packed with accounts of successful practice that has impacted upon children’s RfP.

- Kucirkova, N. and Cremin, T. (2020) Children Reading for Pleasure in the Digital Age: Mapping Reader Engagement London: Sage

A scholarly text with practical advice for nurturing children’s engagement with the written word in this new media age.

- Cremin, T., Mottram, M., Collins F.M., Powell, S. and Safford K. (2014) Building Communities of Engaged Readers: Reading for pleasure London and NY: Routledge.

A practical book documenting the insights from the’ Teachers as Readers’ project and ways to enrich practice.

Teresa Cremin is Professor of Education (Literacy) at The Open University, UK, and co-Director of the Literacy and Social Justice Centre which creates space for research, practice and advocacy to enrich educational opportunities for all. Teresa is an ex-teacher and pre-service lecturer. Her research focuses on volitional reading and writing, teachers’ literate identities and creative pedagogies. A Fellow of the English Association, the Academy of Social Sciences, and the Royal Society of the Arts, Teresa is a currently a Trustee of the UK Literacy Association, a Great School Libraries Champion and an appointed DfE Reading for Pleasure expert. Teresa is passionate about developing readers for life and leads a professional user-community website and wider movement to support the development of children’s and teachers’ reading for pleasure https://ourfp.org/"

References

Allington, R. (2014) ‘How Reading Volume Affects both Reading Fluency and Reading Achievement’ International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 7(1), p.13–26.

Bishop, R.S. (1990) ‘Mirrors, Windows and Sliding Glass Doors’ Perspectives: Choosing and Using Books for the Classroom. 6(3.)

Clark, C. and Teravainen, A. (2017) ‘Celebrating Reading for Enjoyment: Findings from our Annual Literacy Survey 2016’ London: National Literacy Trust

Clark, C. and Teravainen-Goff, A. (2020) ‘Children and young people’s reading in 2019: Findings from our Annual Literacy Survey’ Available at: https://cdn.literacytrust.org.uk/media/documents/Reading_trends_in_2019_-_Final.pdf (Accessed: 16/01/2021).

Cremin, T., Mottram, M., Collins F.M., Powell, S. and Safford K. (2014) Building Communities of Engaged Readers: Reading for pleasure London and NY: Routledge.

Cremin, T. (2019) ‘Reading Communities: what, why and how?’ Manchester: NATE Primary Matters https://cdn.ourfp.org/wp-content/uploads/20210301105855/Reading_Communities_TCremin_2019.pdf?_ga=2.59134382.245682993.1632677737-2008111907.1613423023

Department for Education (DfE) (2013) ‘National curriculum in England: primary curriculum’ https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-curriculum-in-england-primary-curriculum (Accessed 30/4/20) ––(2020) ’The Reading Framework: Teaching the foundations of literacy’ London: DfE

DfE English Hubs (2021) ’Reading for Pleasure Provision Audit’ London: DfE

Farshore (2020) ‘Children’s Reading for Pleasure’ Available at http://s28434.p595.sites.pressdns.com/site-farshore/wp-content/uploads/sites/46/2021/03/Reading-for-Pleasure-2020-Farshore.pdf (Accessed: 14/9/21)

Farrar, J. (2021) ‘“I Don’t Really Have a Reason to Read Children’s Literature”: Enquiring into Primary Student Teachers’ Knowledge of Children’s Literature’ Journal of Literary Education 4, p.217–236

Hempel-Jorgensen, A., Cremin, T., Harris, D. and Chamberlain, L. (2018) ‘Pedagogy for reading for pleasure in low socio-economic primary schools: beyond ‘pedagogy of poverty’?’ Literacy 52(2), p.86–94

Jerrim, J. and Moss, G. (2018) ‘The link between fiction and teenagers’ reading skills: International evidence from the OECD PISA study’ British Educational Research Journal 45(1), p.181–200

McGrane, J., Stiff, J., Baird, J., Lenkeit, J. and Hopfenbeck, T. (2017) ‘Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS): National Report for England’ Oxford: OUCEA and DfE

McQuillan, J.L. (2019) ‘The Inefficiency of Vocabulary Instruction’ International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education 11(4) p.309-318

Merga, M.K. (2016) ‘“I don’t know if she likes reading”: Are teachers perceived to be keen readers, and how is this determined?’ English in Education 50(3) p.255–269

Moses, L. and Kelly, L.B. (2016, 2018) ‘‘We’re a little loud. That’s because we like to read!’: Developing positive views of reading in a diverse, urban first grade’ Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 18(3) p.307–337

––(2019). ‘Are They Really Reading? A Descriptive Study of First Graders During Independent Reading’ Reading & Writing Quarterly 35(4), p.322–338

Mullis, I.V.S., Martin, M.O., Foy, P. and Hooper, M. (2017) ‘PIRLS 2016 International Results in Reading’ Available at: http://timssandpirls.bc.edu/pirls2016/international-results/ (Accessed: 27/7/21).

NUT (2016) ‘Getting everyone reading for pleasure’ London: NUT

OECD (2019) ‘PISA 2018 Results (Volume II): Where All Students Can Succeed’, Paris: OECD Publishing, PISA https://doi.org/10.1787/b5fd1b8f-en

––(2021) ‘21st-Century Readers: Developing Literacy Skills in a Digital World’ Paris: OECD Publishing, PISA

Orkin, M., Pott, M., Wolf, M., May, S. and Brand, E. (2018) ‘Beyond Gold Stars: Improving the Skills and Engagement of Struggling Readers through Intrinsic Motivation’ Reading & Writing Quarterly 34(3) p.203–217

Stanovich, K.E. (1986) ‘Matthew Effects in Reading: Some Consequences of Individual Differences in the Acquisition of Literacy’ Reading Research Quarterly 21(4) p.360–407

Torppa, M., Niemi, P., Vasalampi, K., Lerkkanen, M.K., Tolvanen, A. and Poikkeus, A.M. (2020) ‘Leisure Reading (But Not Any Kind) and Reading Comprehension Support Each Other – A Longitudinal Study Across Grades 1 and 9’ Child Development 91(3) p.876–900

Extend your Read & Respond classroom library

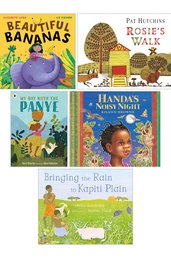

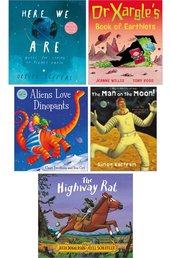

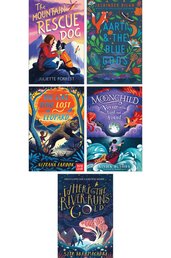

Created in collaboration with the Open University Reading for Pleasure team of expert teachers, our new What to Read After… packs provide a selection of picture books, non-fiction and chapter books linked to your Read & Respond class read, helping you to promote self-selection and reading for pleasure among your pupils.

Discover more-

5books

What to Read After: Jasper's Beanstalk (5 Copies)- gbp prices

- Rewards price: £36.95

- Offer price: £31.00

-

5books

What to Read After: Handa's Surprise (5 Book Set)- gbp prices

- Rewards price: £38.95

- Offer price: £33.00

-

5books

What to Read After: Aliens Love Underpants (5 Book Set)- gbp prices

- Rewards price: £39.95

- Offer price: £34.00

-

5books

What to Read After: The Girl who Stole an Elephant (5 Book Set)- gbp prices

- Rewards price: £38.95

- Offer price: £33.00

-

5books

What to Read After: We Sang Across the Sea (5 Book Set)- gbp prices

- Rewards price: £37.95

- Offer price: £32.00

-

5books

What to Read After: Superworm (5 Book Set)- gbp prices

- Rewards price: £38.95

- Offer price: £33.00

-

5books

What to Read After: Owl Babies (5 Book Set)- gbp prices

- Rewards price: £38.95

- Offer price: £33.00

-

5books

What to Read After: Look Up (5 Book Set)- gbp prices

- Rewards price: £36.95

- Offer price: £31.00

-

5books

What to Read After: Varjak Paw (5 Book Set)- gbp prices

- Rewards price: £39.95

- Offer price: £33.00

-

5books

What to Read After: We're Going on a Bear Hunt (5 Book Set)- gbp prices

- Rewards price: £38.95

- Offer price: £33.00

-

5books

What to Read After: Charlotte's Web (5 Book Set)- gbp prices

- Rewards price: £35.95

- Offer price: £31.00

-

5books

What to Read After: Stick Man (5 Book Set)- gbp prices

- Rewards price: £38.95

- Offer price: £33.00

-

5books

What to Read After: Oliver's Vegetables (5 Book Set)- gbp prices

- Rewards price: £38.95

- Offer price: £33.00

-

5books

What to Read After: Zog (5 Book Set)- gbp prices

- Rewards price: £37.95

- Offer price: £32.00

-

5books

What to Read After: Goodnight Mr Tom (5 Book Set)- gbp prices

- Rewards price: £37.95

- Offer price: £32.00

-

5books

What to Read After: How to Train Your Dragon (5 Book Set)- gbp prices

- Rewards price: £39.95

- Offer price: £34.00

-

5books

What to Read After: Brightstorm (5 Book Set)- gbp prices

- Rewards price: £44.95

- Offer price: £38.00

-

5books

What to Read After: Windrush Child (5 Book Set)- gbp prices

- Rewards price: £37.95

- Offer price: £32.00

-

5books

What to Read After: George's Marvellous Medicine (5 Book Set)- gbp prices

- Rewards price: £41.95

- Offer price: £36.00

-

5books

What to Read After: Bill's New Frock (5 Book Set)- gbp prices

- Rewards price: £35.95

- Offer price: £30.00

-

5books

What to Read After: Winnie the Witch (5 Book Set)- gbp prices

- Rewards price: £38.95

- Offer price: £33.00

-

5books

What to Read After: Carrie's War (5 Book Set)- gbp prices

- Rewards price: £36.95

- Offer price: £31.00

-

5books

What to Read After: Silence is Not an Option (5 Book Set)- gbp prices

- Rewards price: £44.95

- Offer price: £38.00

-

5books

What to Read After: Percy Jackson and the Lightning Thief (5 Book Set)- gbp prices

- Rewards price: £39.95

- Offer price: £33.00

-

5books

What to Read After: Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (5 Book Set)- gbp prices

- Rewards price: £38.95

- Offer price: £33.00

-

5books

What to Read After: Why the Whales Came (5 Book Set)- gbp prices

- Rewards price: £38.95

- Offer price: £33.00

-

5books

What to Read After: The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents (5 Book Set)- gbp prices

- Rewards price: £35.95

- Offer price: £31.00