Voices in Children’s Fiction: Raising awareness for International Stammering Day

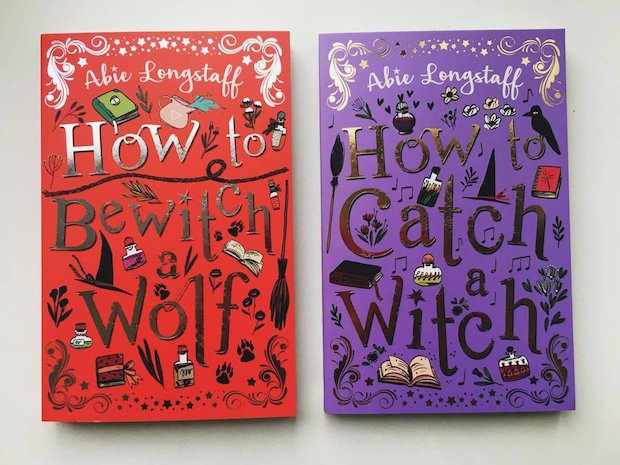

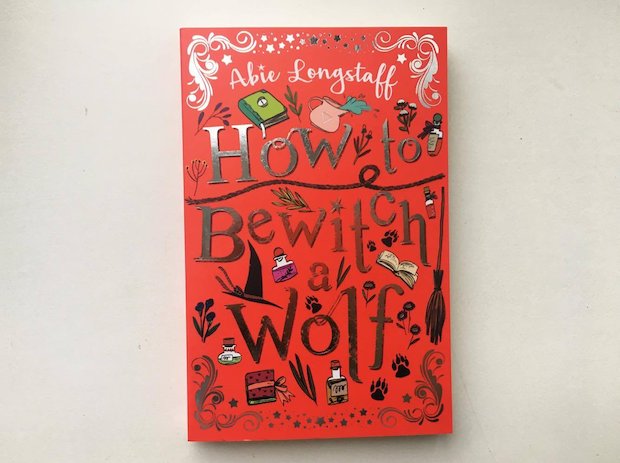

As part of International Stammering Awareness Day (22nd October), best-selling children’s author, Abie Longstaff, describes the background research for her latest Scholastic publication, How to Bewitch a Wolf, and the importance of inclusion and diversity in her work. How to Bewitch a Wolf is the magical sequel to How to Catch a Witch and is just as quirky, funny and enchanting!

I have loved writing the How to Catch a Witch series. Not only has it been a fun adventure, full of magic and excitement, but it has allowed me to spend time in the head of an 11 year old. Year 7 is a tricky time. Your body is changing, and you are still deciding how to view yourself, and the person you want to become. It’s often a time of friendship issues, of learning to fit in (or stand out).

My main character, Charlie, moved schools right in the middle of Year 7. She knows no one, feels lost and confused and, with terrible timing, her stammer has decided to return. She’s petrified she’ll be asked to speak so she keeps her head down to avoid everyone: walking through the corridors pretending she has somewhere to be, or hiding in the library. The dilemma is not that unusual, but Charlie’s solution is a little extreme – her plan is to find a witch and magic away her problems. Somewhere on the way she’ll have to realise that it’s not just her who feels like this, and that a stutter is not a curse.

Diversity has always been a strong part of my writing. I firmly believe that all children should have a chance to see themselves in a story, and in the Fairytale Hairdresser books, illustrator Lauren Beard and I take care to have fairies, princes, princesses and dwarves who come from all over the world.

However, I don’t write “issue books” and in How to Catch a Witch and How to Bewitch a Wolf I didn’t want to write a story where a character ‘fixes’ her stammer, or to give any kind of self-help at all. I didn’t aim to write about a stammer; I simply wrote a book in which my character had a stammer. Charlie was my focus and she needed to have a strong, exciting adventure and become more confident and happy on the way. She has a stammer at the start AND at the end of the book; the only difference is that she learns to be proud of how she speaks, to make friends, and to communicate in her own style.

But was this approach ok?

Whenever authors include important subjects in their books it is crucial they do proper research. We don’t want to portray someone incorrectly or give the wrong message – especially in a book for children. So I began by reading and learning. I watched everything I could online (this TED talk by Megan Washington) and I spoke to the people who know. I contacted Cherry Hughes at the British Stammering Association, and Elaine Kelman at the Michael Palin Centre. Both were fantastically helpful. I had so many questions! Can a stammer come and go? How does stress affect it? How does it make someone feel? And above all – is it ok that, at the end, Charlie accepts her stammer, sees it as part of her; it’s not an ‘illness’ or affliction, it’s just the way she speaks. She doesn’t stop stammering but she finds peace with the way she talks and makes friends who accept her the way she is. To my great relief, Elaine said yes – this was a good message. And, as teacher Abed Ahmed says: ‘the quicker you accept your stammer, the quicker you can move on’.

What I also learned was: there are very few fiction books for this age group that portray a stammer positively. Despite the number of people who stammer (roughly 1% of the population – over 70 million!) and despite the fact that stammering is an issue affecting children from all cultures and backgrounds, there is very little awareness or understanding on the subject. All this made me more determined than ever to get this series right. But not so that I could show off my research – so that I could make a relatable, and engaging character.

In this respect, I’m happy that so many reviews don’t mention Charlie’s stammer at all. They just talk about the adventure:

‘This spooky tale about witchcraft and ancient traditions is an engaging combination of spells, potions, friendship and self-belief.’

Book Trust

‘Longstaff works her trademark magic in this warm, witty fantasy story about friendship, sharing and identity. Totally bewitching!’

Lancashire Evening Post

‘I adored How To Catch A Witch_ from the first line and I didn’t want to put it down… Abie writes beautifully. Her descriptive language sucks you into the story, grabbing hold of you until the very last page. The book has a real classical feel to it. It would have been a firm favourite with me as a child’_

Serendipity Reviews

At the same time it is wonderful to receive recognition from those with an inside view of Charlie’s situation:

‘It’s so refreshing to have a strong and interesting main character who stammers. Charlie, an 11-year-old girl, has adventures in a magical setting that will fascinate any young reader. Through these adventures Charlie learns to accept herself as the person she is and her stammer as part of that. This book gives out the best possible message about stammering, and engages the reader with its excitement and fantasy from the very first page.’

Cherry Hughes, Education Officer, British Stammering Association

‘It is wonderful to read a book which is fun and interesting and which also has a central character who stammers who is not defined by her stammer. Our therapy with children and their parents is helping them to see that they can be confident communicators with or without a stammer. Charlie brings that to life through the pages of this book.’

Elaine Kelman, Consultant Speech and Language Therapist, The Michael Palin Centre.

I love knowing that I’ve made a book where a stammer isn’t a disability; so my Charlie can proudly say (as the amazing school kids do in this video https://youtu.be/nalMre18ruA)

‘This is my voice’.

An Extract from How To Bewitch a Wolf

With her stomach churning, Charlie pushed the door open. A sea of faces looked up. “Um… I’m, uh…” she stumbled over her first words. Everyone stared. The teacher waited, expectantly. Charlie opened her mouth but, to her horror, she found she couldn’t say the “ch” of her name.

There was a long pause. Charlie could hear her name inside her head but it was like the sounds were stuck in quicksand: the more she tried to pull them out, the deeper they sank. She tried the “ch”, “ch” for Charlotte. She screwed up her face, willing the word to come. There was a giggle from the back of the class.

“Rumpelstiltskin!” a boy shouted and everyone laughed.

Charlie’s cheeks were growing hot and she could feel tears prickling at the back of her eyes. In desperation, she tried her surname: “SSSSamuels,” she burst out, a little too loudly.

Realization hit the teacher. “Oh,” Miss Robbins said as she shuffled through the pieces of paper on her desk. “I have a Charlotte on my list,” she said slowly, as if Charlie was stupid. “Is that you?”

Charlie nodded miserably.

Similar Posts

-

What’s new this October!

Discover this month’s new books, spanning heartwarming picture books, exciting stories and lot’s of festive tales!

-

The benefits to humour in children’s fiction, by Emily-Jane Clark

Author Emily-Jane Clark discusses the benefits of humour in children’s fiction and shares her reasons for writing funny stories.

-

Read this summer with Luna Wolf!

Now the sun is shinning, read this summer with Luna Wolf: Animal Wizard by superstar TV presenter and bestselling children’s author Alesha Dixon! Discover our list of fantastic books we recommend to read alongside _Luna…